Of craftspeople, tinkerers and inventors

When Mario Klötzer, technical manager at Mühle, looks at a machine, he’s not just trying to find out whether everything is in working order. It’s always also a question of thinking about if things could run even better. If “we’ve always done things this way” were the company’s motto, it’s unlikely that it would have been so successful. Striking a balance between expertise and the joy of experimentation is something that Mühle has in common with other traditional manufactories, of which there are many in Saxony.

“I don’t think it’s sustainable just to preserve and keep things that are traditional going. On the one hand, manufacturing must preserve knowledge and remain committed to values such as quality and durability. On the other, they must keep on reinventing themselves in line with the times. Design and sustainability play a greater role today than ever before,” says Mühle CEO Andreas Müller.

For generations, knowledge and skill have been passed on here to produce such diverse products as writing implements, barometers and wooden Christmas angels at the highest level. The watches from Glashütte and porcelain from Meissen are famous around the world. Preserving tradition requires steadfastness, at times even a certain stubbornness. Guiding tradition into the future requires something else.

The Leipzig cabaret artist Bernd-Lutz Lange puts it thus: “The Saxons have always been craftspeople, tinkerers and inventors. From Chlorodont to the bra to filter bags, all of these things were invented here.” The facts prove him right. Saxony has the highest density of engineers in Germany, and Saxony’s universities have yielded the most patent applications. What does that mean in concrete terms?

Where people really get stuck in

There are ten watch manufacturers for every 7000 inhabitants in the small town of Glashütte in the Eastern Ore Mountains, surrounded by forests and hills. Nowhere is Saxon craftsmanship as apparent as here. Lange & Söhne is based here, as are Glashütte Original and Tutima. High-quality watches have been manufactured in the Müglitztal since 1845, and the place is a mecca for watch lovers all over the world. The “Glashütte rule” stipulates that at least 50 percent of the added value be created here – so no one can give themselves the name “Glashütte” but then outsource production to other places.

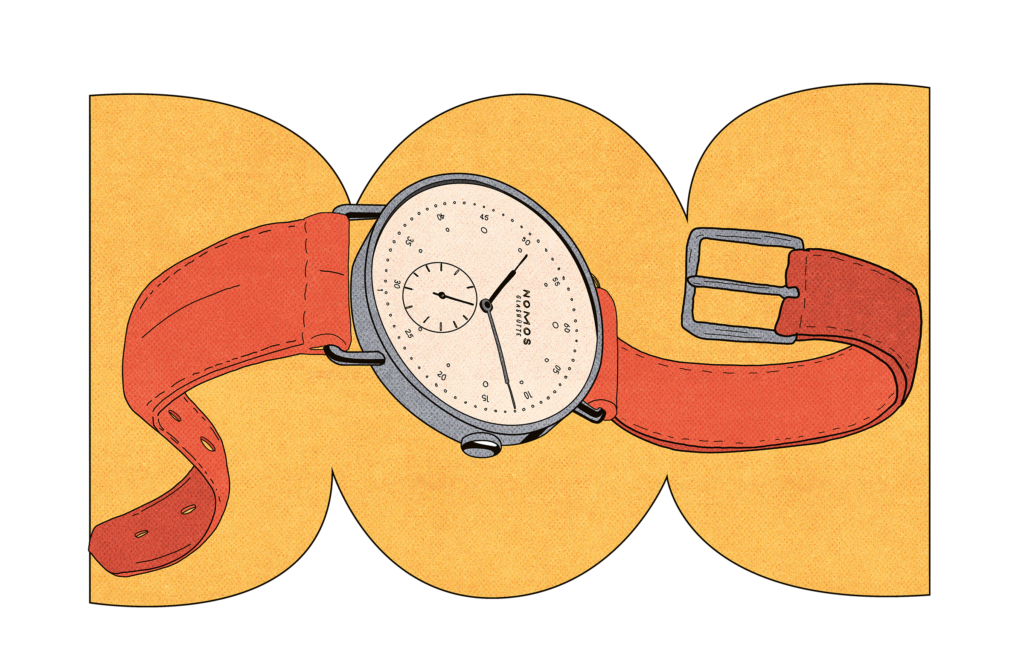

Nomos is situated right next to the railway tracks. Its employees are beavering away as if their lives depended on it. Nomos isn’t a traditional manufacturer in the strict sense of the term, having only been on the scene since 1990, when it was founded by Roland Schwertner, an IT expert from Düsseldorf who had heard about the town’s watchmaking expertise. Uwe Arendt and Judith Borowski later joined as co-managing directors. With purist Bauhaus-oriented design and high-quality technology at affordable prices, they made Nomos the most successful German watch brand.

“Glashütte is a kind of Switzerland in miniature,” says Judith Borowski. “The technical expertise that we have here, the will to dig deep, the collaboration with universities to drive forward technological developments – all of this is unique.” With the help of outstanding technical expertise, Nomos was able to develop a particularly flat mechanism, which suits the slim elegance of the watches it aims to produce. “We use traditional knowledge,” says Borowski, “but we push the boundaries, linking it up with the world of tomorrow”.

Where manufactories have been supported by the state for centuries

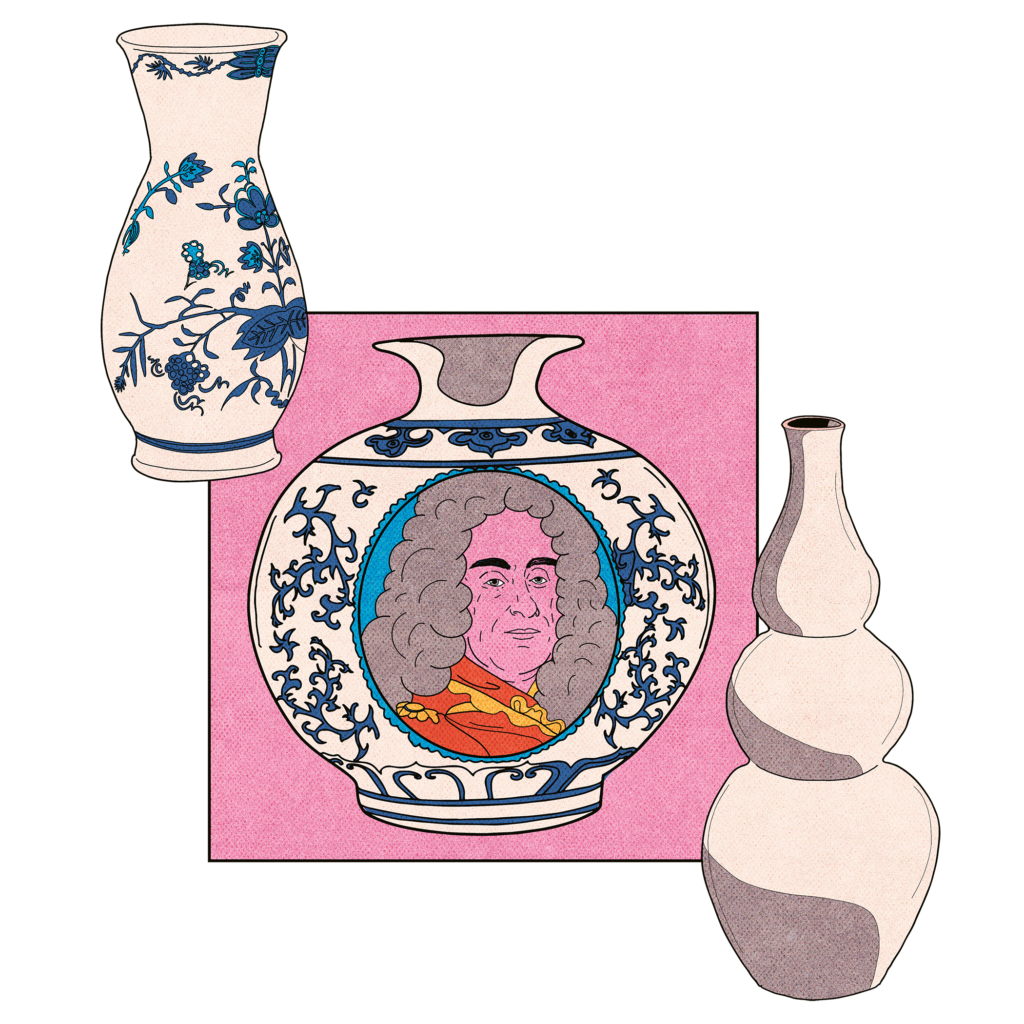

From Glashütte to Meissen. Meissen Porzellan, the oldest and probably best-known manufactory in Saxony, is based here. The history of porcelain production is a good illustration of why the manufactory scene in Saxony is so pronounced.

Prince August II of Saxony, born in 1670 and given the title “the Strong”, suffered, by his own account, from the “maladie de porcelaine”. He had an almost pathological obsession with porcelain, which he purchased for expensive prices in China, but no one in Europe knew how to make it. So he summoned the alchemist Johann Friedrich Böttger, who had allegedly managed to produce gold, to his court. The Prince needed such knowledge to bankroll his expensive lifestyle – not to mention his passion for porcelain. The story about the gold turned out to be false, but the alchemist Böttger did indeed find the formula for developing porcelain, and in 1710 Augustus the Strong founded the first porcelain manufactory in Europe. He didn’t stop there, but arranged for production plants to be set up for fabrics, paints, rifles and astronomical instruments. He was also a great supporter of the Leipzig Trade Fair, which was founded as a trading centre as early as the Middle Ages. Export goods “Made in Saxony” were intended to fill the state coffers.

The promotion of state manufactories had been practiced by other absolutist rulers before the Prince – especially in France. The term “manufactory”, which today sounds like the good old days, like premium products manufactured under fair conditions, once stood for ruthless capitalism. By gathering various trades under one roof and also breaking down a craft into highly specialised fields, it was possible to optimise product quality and bring down the cost of production. The most important innovation of this type of production facility was that the means of production were no longer in the hands of the craftsmen.

Today, Meissen porcelain is a cultural asset promoted by the state of Saxony, which is still the manufactory’s owner. “The manufacturing process has been handed down for 300 years,” says Tillmann Blaschke, Managing Director at Meissen. “The material kaolin still comes from our own mine,” he says. Shaping and painting have also barely changed.

Teaming up

When it comes to design, however, Meissen is definitely looking to keep up with the zeitgeist, embarking on unexpected collaborations such as with New York skater label Supreme. Together, they released the limited-edition plastic “Cupid with Shirt”. “When the venerable old lady Meissen sits down at the same table with the young folks from Supreme – that’s an exciting meeting of minds”, says Blaschke and laughs. Meissen and Mühle have also already teamed up and developed a shaving set with a painted porcelain handle. “Every company has its history, its pride, its place in the market, and it’s a beautiful thing when two companies team up,” says Blaschke. If you get the choice of partner right, such cooperation is a successful strategy for leading a brand into the future without breaking with tradition

This article was first published in the spring 2022 print edition of 30 Grad.