Fjords of fabric

The clouds are low this morning. The myriad green tones of the Mourne Mountains can still be seen, but the inlet at their base which separates Northern and Southern Ireland remains hidden. It is nine o’clock and Mario Sierra strolls gently down the mountain to the workshop where his employees are arriving. They sit at the old wooden looms and begin to work the treadles. As a child, he used to come and play in the Mournes. Now in his 40s, he has come to make new plans for his business.

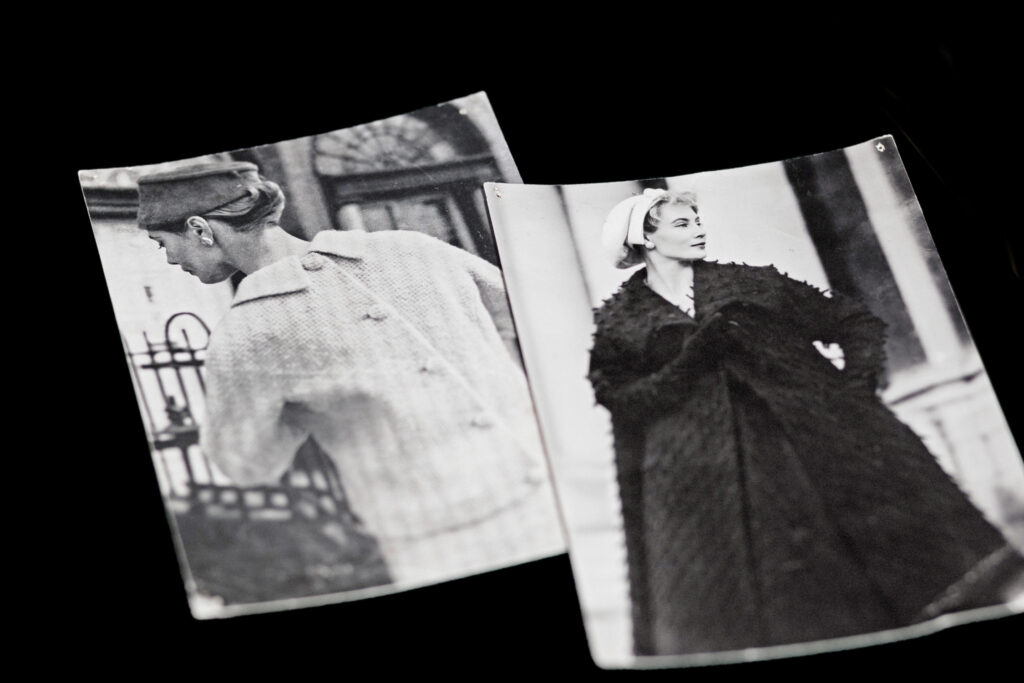

Three years ago, Mario Sierra decided to re-open the weaving mill that was first opened in 1949 by his grandmother. He describes his grandmother as a strong, visionary woman. Gerd Hay-Edie was born in Norway. She studied Design and travelled throughout Europe, setting up a weaving mill in Northern Spain, making tapestry, and also working in England for several companies as a designer. She sought out a peaceful location and settled here in Rostrevor in 1947, with the intention of opening a design studio. Because there were no weavers to make her designs, she decided to manufacture them herself, and founded Mourne Textiles. And she became very successful. In 1951, renowned British furniture designer Robin Day took one of her carpet designs to La Triennale in Milan. So began a long-standing partnership with furniture manufacturer Hille, who also manufactured Day’s famous polypropylene chair. Irish fashion designer Sybil Connolly was a fan of Hay-Edie’s tweed designs and adopted some for her collection. Business was booming. But the Northern Ireland conflict continued to escalate throughout the 1960s. “From one day to the next, people just stopped coming to the area. This is the border region. Suddenly the army were everywhere. It was as if we had been cut off”, says Sierra. At the same time, textile companies started outsourcing production to the East. Ireland’s once prosperous wool and linen industry could not keep up with cheap competition from Eastern Europe, India and China, and many production facilities were forced to close. Nevertheless, Sierra’s grandmother and his mother, Karen Hay-Edie, tried to somehow keep the business afloat. Only in the 80s did they give up.

Upon arriving at the workshop, Mario Sierra must first of all put some more wood on the fire. Once again, the heating is not working. “This is an old house,” he says. “It is nice to be able to spend so much time here again.” In the meantime, he travelled the world. He wanted to travel, and see life beyond this village with its population of 2,500. He studied Textile Art at the Winchester School of Art, moved to London, worked as a sound engineer, and started a family. Then, one afternoon three years ago, his mother called. She told him that she wanted to sell the looms. Sierra immediately replied: “No way!”

Memories from his childhood came flooding back. He remembered the workshop as his “happy place”, his playground and his place of refuge. As a small boy, he felt safest under the looms, and often slept there too. And he thought about his grandmother, who died in 1997. She had taught him how to weave. As a teenager he would sometimes spend days working on a blanket or a rug. If there was even the smallest mistake, his grandmother would say: Start again! She would not tolerate any mistakes, and nor would the customers. “She was the toughest teacher. And the best,” he says. He really wanted to bring this place back to life, fill it with people, and get the machines running.

Sierra says the beginning was like flying blind. “I had no idea what I was letting myself in for!” He had not anticipated the complications involved in setting up a functioning network in the industry that was once so important for Ireland. “Many of the good players have no online existence, so you can’t just google them. ” But he needed answers to questions such as: Who supplies the best wool? And the best yarn? Where can you have finished woven fabrics washed? Are there any experts left, and if so, where are they?

But he was also fortunate. His re-opening came at the right time. Old handicrafts are in demand. The recurring headlines on intransparent production conditions in the textile industry have increased the demand for fair local products. In addition, more and more people are yearning to get away from constantly working with computers, keen to make things with their own hands instead. This resurgence of interest in traditional craftsmanship is not confined to Ireland. Over the last few years, we have seen the emergence of international do-it-yourself portals like Dawanda. Ecological fashion labels are now considered chic. Great Britain and Ireland have been at the forefront here, with their self-organised Crafts Council. The government established the Arts Council England, which in turn also co-organises the week-long London Design Festival.

Mario Sierra now commutes between London and Rostrevor. And in the meantime, the factory with the old wooden floors and plenty of patina has again become the workplace of six permanent and three freelance employees. This morning is very busy, with almost all of the 12 looms in operation. It can take days or weeks of handwork for the weavers, some trained, some self-taught, to create the black and white striped rugs and scarves, the apple-green blankets and pink cushion covers for which Mourne Textiles has since become famous. “You can just tell when a fabric has been hand-woven,” says Sierra proudly. “People now appreciate that again.”

Some small, lucky coincidences have also helped, such as the one with Jamie Oliver. The British celebrity chef recommended Mourne Textiles to his Instagram fans. “Check these guys out,” he wrote. As a result, within 24 hours, Mourne had 6,000 new followers. Sierra considers social media to be hugely important: “Designers and architects find us there.” In the meantime, nearly 10,000 people now follow his Instagram activities.

“I just don’t want to fall into the hipster trap,” he says. For him, it is not a question of creating hype. His vision for Mourne Textiles goes beyond short-lived trends. Together with his mother Karen, he would like to work out the techniques necessary to manufacture all of the designs in the books left behind by his grandmother. “I am sure that will become valuable one day.” And he wants more recognition for his grandmother’s work. Sometimes he believes that she and her talent became somewhat lost here in the Mournes. With this work they would not only perpetuate the work of Gerd Hay-Edie, but also her beloved Mourne Mountains. “Many people say that my grandmother settled here because the mountains look like the fjords of her Norwegian homeland,” says Sierra. “I think that the Mournes, with their many colours and different surfaces and textures, look just like her hand-woven fabrics.”

This article was first published in the spring 2016 print edition of 30 Grad.