You’ll never walk alone

The sky hangs low over St Michael’s Road. Small houses, which have seen better days, stand in endless rows. The headquarters of the traditional manufactory Tricker’s are right among them. The company was founded in 1929 and has been owned by the same family for five generations now.

With its intarsia-decorated glass windows, the building has a slightly playful guise. In 1903, conceptions of industrial architecture were different. When the factory was built, Tricker’s was the flagship of the booming shoe industry. At the end of the 19th century, Northampton was the shoe-making capital of Europe with over 2000 manufacturers. 100 million pairs of shoes were produced here. In the 1970s, cheap Asian imports led to a big decline and over the next 20 years, more than 10,000 jobs were lost.

Scott McKee leads the way across steep and winding stairs, past shelves full of wooden strips and furled leather hides and rattling sewing machines. McKee is master shoemaker and factory manager, part of the company for over 23 years. At the age of 15, he followed in his dad’s footsteps, who was a shoemaker himself. Many here have a similar biography. Boys in Northampton are “born with a leather apron”, so they say. Some of the traditional companies have survived the decline and are successful once again. They include Church’s, Crockett & Jones, Barker, Loake, Joseph Cheaney and also Tricker’s – thanks to the heritage boom and a desire for the “good old things”. Tricker’s managing director Martin Mason is quite the opposite of Scott McKee. He has a cosmopolitan as opposed to a down-to-earth attitude and has had a varied career as opposed to a straight-line CV. For many years, the man in his mid-fifties with shining blue eyes, short grey hair and ironed shirt worked for different companies in the luxury industry. Among them Pringle of Scotland, Mulberry and also MCM, which he was in charge of introducing to the Chinese market. For four years now, he has been the managing director of Tricker’s, the first person not to be a family member since the founding of the company.

“They had definitely reached their limits,” says Martin Mason as he explains the decision. “The Barltrops are a family of traditional shoemakers. They needed someone who had a lot of experience with international marketing and brand building.” Someone like him. The last director, Nicolas Barltrop, has retired from the day-to-day running of the business. What’s the most decisive change since then? “When I joined, Tricker’s was a factory with a brand. Now it’s a brand that has its own factory.”

For Mason, the work at Tricker’s isn’t just a job. He feels connected to the company. “We have a heritage which we are really proud of here,” says Mason. “Our products have a soul.”

This is why Mason was careful not to change classics like the Malton boot or the Bourton brogue or even employ a designer. It’s these classics that win new customers. As a company which stays true to its style and sells shoes that last a lifetime, it’s important to gain new customers. “The most important thing is to change as little as possible,” says Mason. “The DNA is crucial.” Communicating this aspect has been his first objective. He has modernised the company’s online presence, hired a PR agency and improved social media communications. Tricker’s now has 75,000 followers on Instagram. “We have a story which is worth telling.”

Both Mason and McKee love good stories, and sometimes they both tell the same one. For example, the one about the two things that no man should skimp on: a good bed and a good pair of shoes. An piece of advice that McKee supposedly received from his father. “He got it from me,” says Mason, contradicting him.

It doesn’t actually matter who’s right. It’s about cultivating an image. The robust shoes, which were almost exclusively worn by farmers at the beginning of the 20th century, before the landed gentry and later the townsfolk discovered them, are premium craftsmanship; their quality is beyond reproach. Nevertheless, they face global competition, including with products with huge marketing budgets.

Another careful change that was introduced by Mason are seasonal collections. Where forms and models remain unchanged, colours and materials may vary. Kudu leather, an African antelope species, or “Olivia” – olive-tanned leather from Italy – are used. However, Tricker’s never tries to be fashionable. “Certainly not,” says the director. “This is not about fashion but relevance.” Scott McKee has a lot of work to do in the office, however, he always returns to his workspace on the third floor, to the bespoke shoes. Pinned down to the lasts with many small nails, a half-finished piece of wonderful craftsmanship awaits his skilled treatment. Wooden lasts for bespoke customers are piled on a shelf, some of which have been here for decades. Upon closer inspection, it becomes obvious that bespoke shoes aren’t a luxury but a basic necessity. Who would otherwise be able to get shoes in size 55? Or shoes shaped like duck feet? Some of the lasts were adjusted with cork additions as feet tend to change over a lifespan; a bigger ball here, a thicker heel there.

With a steady hand, McKee pulls the heavy hammer across the upper leather in order to push the cap of the shoe into shape. “He’s a gifted shoemaker,” his director acknowledges. People even ask for his autograph during exhibitions in Japan or the men’s trade show Pitti Uomo in Florence. Up here above the rooftops of the city, every tool or production stage could probably have been witnessed 150 years ago.

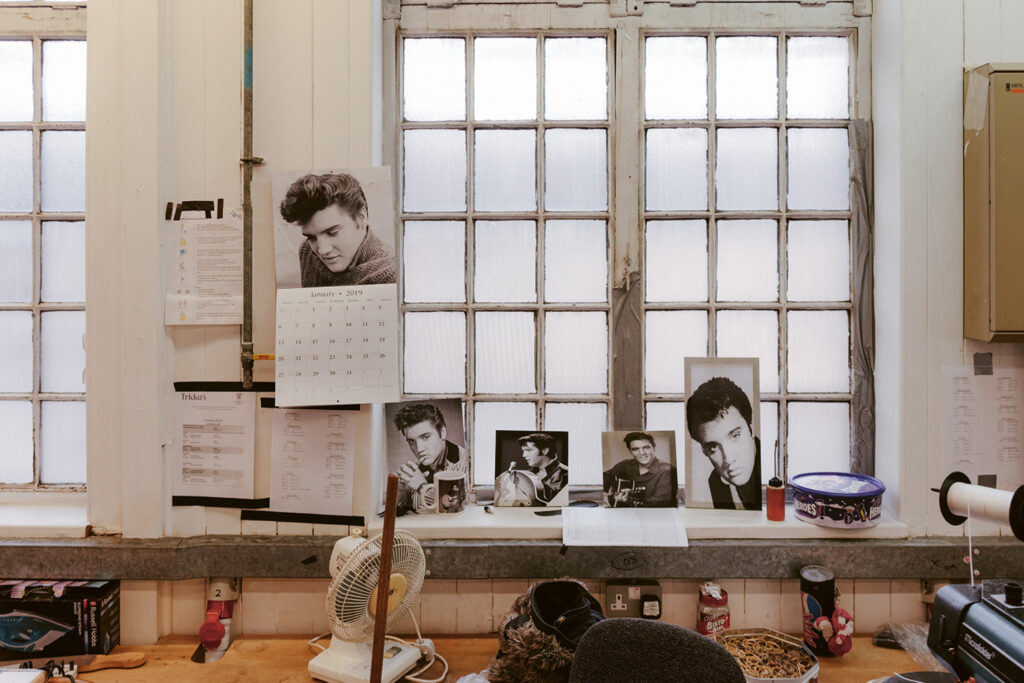

On the lower floors of the building, things tend to be a little less romantic. A variety of radios make just as much noise as the machines. Here, toe caps are pressed into shape with one single steaming hiss. This doesn’t mean that you can be any less than extremely careful when making them. All in all, a pair of Tricker’s is assembled in 260 individual stages.

After the overshoe has been brought into shape, it is given a protective cover, to prevent it from damage during processing. What follows next is the decisive step in shoe production, which makes the difference between a premium and a regular shoe. The overshoe is welted onto a frame or stable leather strip. This frame then forms the connection to the sole. The lock-stitched combination makes for a sturdier shoe and can be unstitched and repaired whenever this is necessary. Charles Goodyear had such a machine patented, hence the name “Goodyear welt”.

In the final step, the heel is attached to the shoe. In some models, a little corner on the inside is missing, the so-called “Gentlemen’s Corner”, which prevents the fabric of your trousers from getting caught on your heels when crossing your legs. Finally, the shoes are polished – four pairs a day can be done by one worker – and packed into boxes. For bespoke shoes, the boxes are lined with velvet. “I call it the sexy box”, saysMcKee with a grin.

Around 1,000 pairs are made per week, which cost about 400 to 500 pounds or 450 to 580 euros. For bespoke shoes, of which only three to five are made per week, customers pay between 2,500 and 3,000 pounds. 80 percent of the production is exported – with 25 percent, Japan is the by far the biggest market – China and Korea are growing fast as well. This year marks the 190th anniversary of the company – there will even be a special edition of a classic – and there’s still plenty of work to do, says Mason. He’s here for the long haul and has just recently bought a house in the area: “Tricker’s is still something of an insider’s tip. You’re not born a Tricker’s man, but once you become one, you will stay one forever.”