Rethinking materials

Text: Anna Schunck

When Julian Nachtigall-Lechner first told me about his idea in 2015, I was thrilled. Making cups from recycled coffee grounds. That makes so much sense! After all, nothing is drunk as readily and frequently around the world as coffee. And waste is left over from every sip brewed. That’s exactly what the Berlin-based product designer demonstrates with his structured cups, which are now available in nearly every coffee shop and concept store in the nation and which fit so comfortably in your hand. Kaffeeform, as Julian’s company is called, was an intelligent reminder to me at the time of our society’s waste problem. Today, new and sustainable materials are more than this: they’re a necessity.

Because our mountains of waste are suffocating us. It sounds harsh, but they’re literally choking us. Since the publication of a WWF study in 2019, we know that we ingest a credit card’s worth of microplastics every week without even noticing it. We consume such microplastics via our lungs in particular. This leads to inflammations in the intestines and liver and increases the risk of developing cancer. Each and every piece of plastic that has been produced since the invention of synthetic materials in the mid-20th century still exists in some form today. Despite this, more and more plastic is being produced. Each person in Germany consumes about 38 kg per capita per year on average.

These are home truths that most of us are just as happy to suppress as the imperishable nature of the material. No wonder! Plastic is ubiquitous and is taken for granted in industry and commerce. After all, what are we supposed to do if we can only buy tomatoes packaged in it? Be ashamed that we buy them anyway? My response is, please don’t! Because we’re living in a material world – and we buy what we can because we can. And speaking of unpackaged tomatoes, we sometimes even have to. We take the products in the shops so much for granted that we’re unable to constantly think about the fact that almost everything we use has to be industrially produced in long elaborate processes.

Unfortunately, most common materials are genuine resource guzzlers when being produced. Plastic is made from petroleum, concrete from clay and limestone, and leather from animal skins. Before the respective materials are ready to use, enormous amounts of energy are consumed, which in turn usually comes from non-renewable sources and is finite. In addition, water and chemical additives leach out soils on which new, better raw materials could actually grow. That may sound like a sobering endless loop at first. But it can also inspire us to rethink how we do things. Because there’s another way! And, very gradually, better alternatives are finally gaining ground.

Better means, put simply, that the materials are produced with as little energy as possible, are pesticide-free and vegan, and consist of regenerative raw materials, whose remains we actually get rid of in the end. Or, ideally, we can continue to use them. More and more often, waste is being turned into something new. Just as coffee grounds are turned into mugs, dog undercoat, which is otherwise thrown away in millions of households after combing pets, is turned into new yarn, or potato peel into plastic. Circular economy is the key concept we should remember for the future. Anything that can be mechanically recycled after its first cycle of use and completely turned back into fresh material is good. And this should, indeed, it absolutely must, be even more the case!

Not only science and research have now recognised this, but also brands and companies that often work closely with material developers – and can quickly make good new materials available to many. That’s great. It’s also good news that the German Government is funding research into this to an increasing extent. But, and this is a question that’s on all of our lips: is that enough? I believe that when it comes to regenerating our planet, it’s never enough. We’ve simply gone too far for that.

Reversing the trend would have to involve drastic measures. Not only do we have to use new materials, but we also have to move away from over-consumption. A systemic change is required. This takes time and cannot be driven by individuals alone. We need fundamental, politically controlled restructuring. This doesn’t mean that each and every one of us should not also question our own consumption – especially when it comes to the life cycle of our products. If we choose, care for, repair, preserve and pass on our products well, then we don’t have to worry about the question of materials on a small scale. And if you don’t buy things just to throw them away again afterwards, you’ve already taken an innovative step in the throwaway society in which we live.

May we introduce?

Research is being conducted, trialled and launched: New, innovative materials are flooding onto the market, backed by research laboratories, universities and companies. Here we present a small selection.

Text: Franziska Klün

Wall panels made with salt

Atelier Luma in Arles in the south of France is a research laboratory that you should keep an eye out for. As part of Roche heiress Maja Hofmann’s gigantic Luma Arles art project, an interdisciplinary team is investigating how new, less environmentally harmful materials can be produced from local resources and with the help of regional handicraft techniques.

The research results of the past few years were unveiled recently, including colourful acoustic plates made of sunflower stems, wall panels and door handles made of sea salt, stackable seat cushions made of algae-based bioplastics, carpets made of palm fronds. They all demonstrate how spectacularly beautiful ecological material alternatives can be. After all, these materials are still perceived – and sometimes rightly so – as being an aesthetically inferior choice. That being said, the products made in Arles are consistently top-notch.

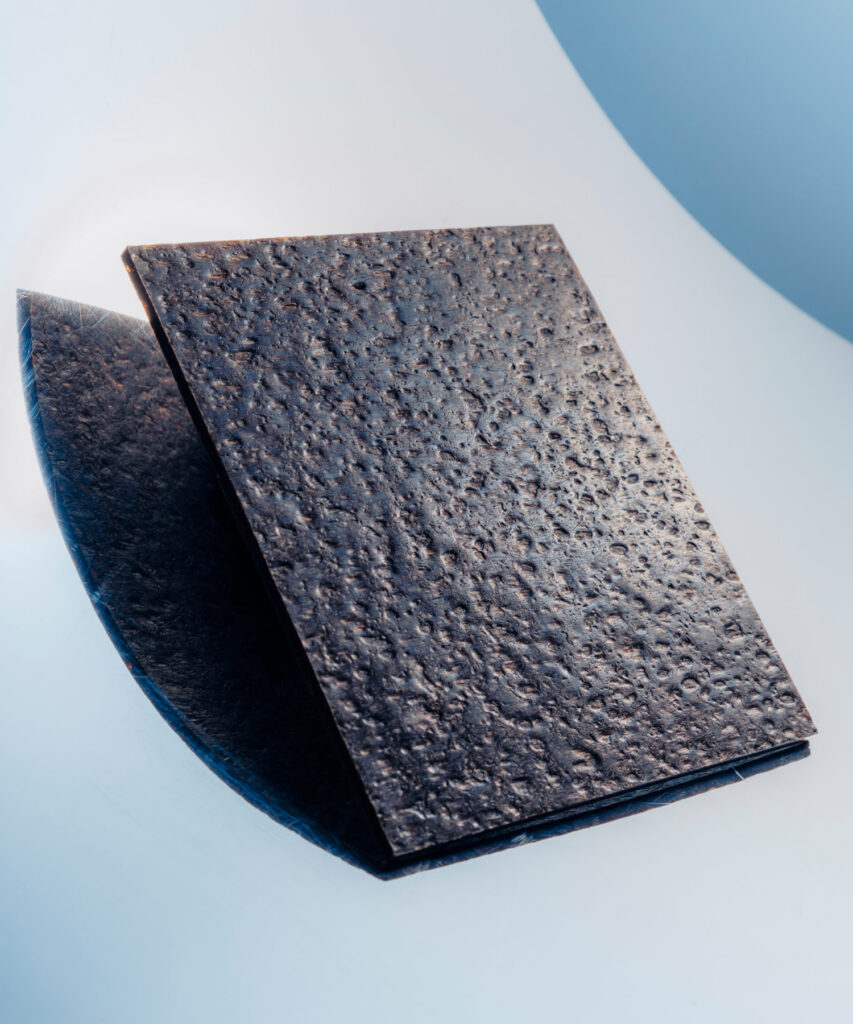

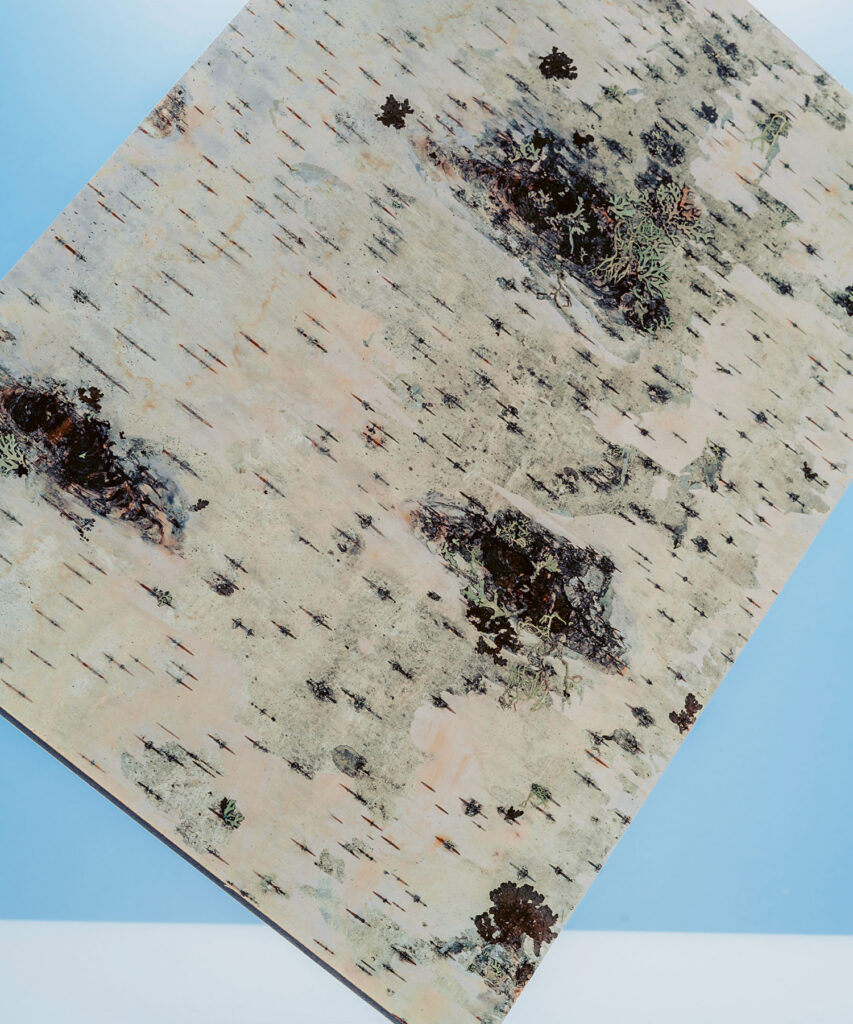

Surfaces made with birch bark

MÜHLE was immediately interested in an innovation made by Nevi, a manufactory from Görlitz. Nevi manufactures water-repellent, robust surfaces made from the bark of Nordic birch trees, which are also suitable for shaving brush handles.For thousands of years, birch bark was about as important from a technical point of view as plastics are today. Nevi CEO Tim Mergelsberg discovered the ancient craft of bark processing in Siberia in 2005 and decided to revive it and adapt it to today’s requirements in the building and design industry.

Low-maintenance birch bark cork can be used for floors, wall coverings and handles of any kind. For the production, the bark is removed by hand once a year from the birch trees that continue to live afterwars. The bark is then pressed, cleaned, trimmed, layered and further processed as part of a patented process. At MÜHLE the material is used in the Rocca series.

Clothes made with wood

Are you familiar with Tencel? The material made from Lyocell fibres was developed back in the 1990s and is something of a classic among innovative textile fibres. Fast-fashion chains like H&M use Tencel, as do sustainable brands like Armed Angels. Compared with other textiles, Tencel has many advantages in terms of sustainability. First and foremost, the fibres are made using wood from trees native to Europe, such as spruce, beech and eucalyptus. Forestry requires neither artificial irrigation nor pesticides or fertilisers, and the trees largely grow on land that’s not suitable for agriculture.

What’s more, the majority of Tencel fabrics used by European brands are made from European wood at the company’s headquarters in Austria and thus – in contrast to cotton, for example – require only short transport routes. If a product is really made of 100 percent Tencel, it’s also 100 percent biodegradable. Despite all these advantages, there’s one snag. Wood is also a finite, valuable raw material, of course, as many of us are painfully aware in times of ailing forests and forest fires.

Art made with plastic waste

Dirk van der Kooij has been fascinated by plastic since childhood. In his studies, the Dutch designer, who is now known for the sculptural nature of his designs, began to experiment with recycling plastic. One of his first projects was the Chubby Chair (see picture p. 20) – a chair made of 100 percent recycled plastic that looks like an oversized children’s chair.

Chubby is produced with a 3D printer made from the melted down interior parts of discarded refrigerators. With sustainability in mind, van der Kooij’s customers are encouraged to bring their own plastic waste to the designer’s studio to produce their own piece of furniture. This also promotes product identification, of course.